Hot in the City: Combatting the Urban Heat Island Effect

As the climate crisis becomes an increasing concern, architects are starting to incorporate design details into projects aimed at mitigating the urban heat island effect. From white coatings to cycle parks and vegetation, Ross Davies looks at some of the most popular strategies

Images courtesy of Perkins+Will

During late July and early August 2008, an intense heatwave hit Oklahoma. At its peak, the mercury rose to 110°F (43.3°C) in the south-midwestern state.

A later study of the heatwave revealed that temperatures in Oklahoma City, the state capital, were, on average, one degree warmer during the day than in the hinterland. Researchers discovered this urban-rural disparity to be even more striking at night, with the city four degrees warmer.

Such findings exemplify a phenomenon known as the heat island effect, whereby concrete-filled, built-up urban areas absorb and trap the sun’s heat – rather than reflecting it – causing temperatures to rise. This is the reason why we tend to feel the heat more acutely in cities than in the countryside.

Throw into the mix heavy traffic and you have the toxic cocktail of increased energy consumption and reduced air quality – which in more densely populated parts of the world, such as South Asia, can be lethal. A case in point, in June last year, New Delhi recorded its highest ever temperature of 48°C, amid a heatwave that killed 36 people.

If heat and humidity levels continue to rise, cities in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh will become uninhabitable by the next century, warns a recent piece of research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

While they are inextricably linked, heat islands and climate change are not one and the same, says Lisa Gartland, an energy efficiency engineer with California-based Proctor Engineering Group.

“The negative effects of heat islands have been noted since the early 1800s – well before there was any inkling about climate change,” she explains.

“Heat islands and climate change are different problems with different causes, but they unfortunately work in tandem to make cities hotter and less liveable. Climate change brings hotter summer weather and more intense heat waves, with hotter conditions then exacerbated by urban and suburban heat islands.”

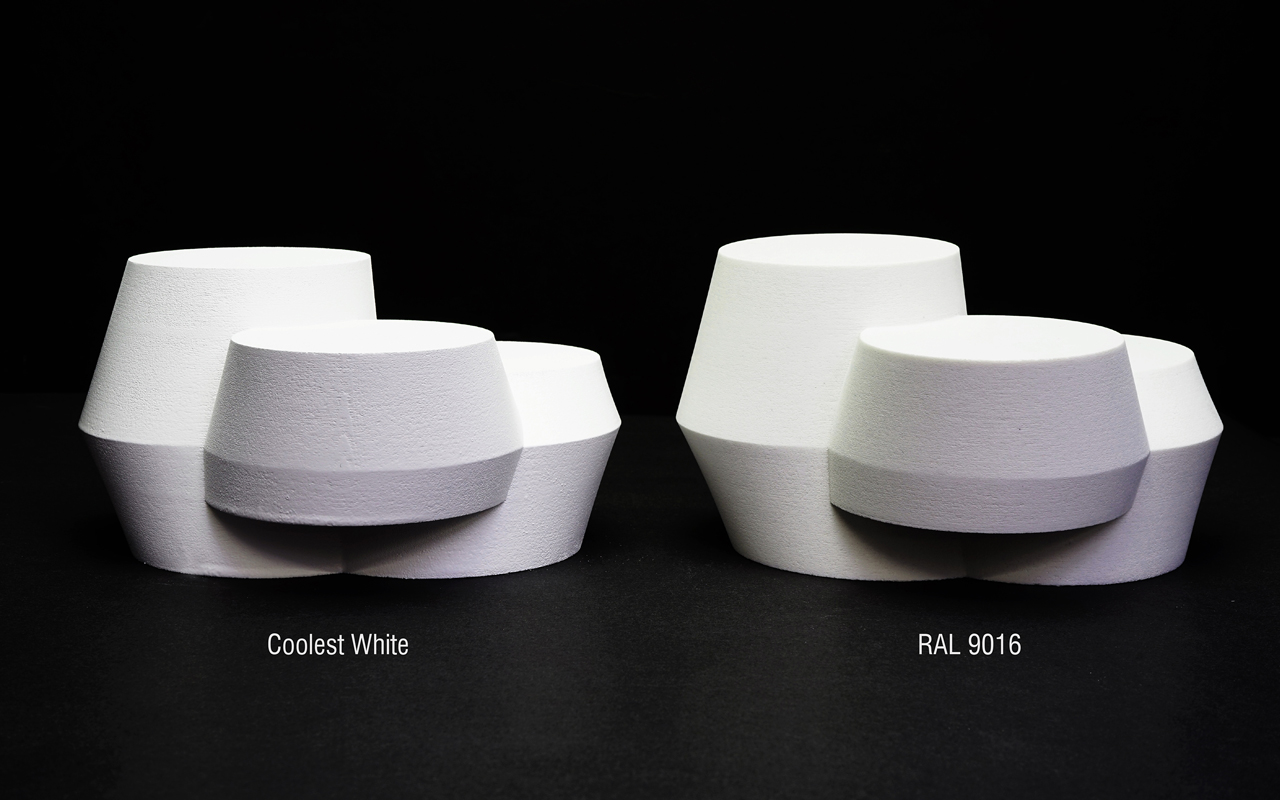

The paint colour Coolest White is designed to reduce absorption and emission of the sun's rays by 12% | Image courtesy of UN Studio

Coolest White is designed to reduce absorption and emission of the sun's rays by 12% | Image courtesy of UN Studio

The paint has been developed by UN Studio in partnership with Monopol Color | Image courtesy of UN Studio

It is based on fluroploymer technology | Image courtesy of UN Studio

Cooling down: Lighter coloured pavements, cool roofs and more trees

For those that can afford it, the go-to recourse for most perspiring city dwellers is the air conditioner remote. But, given that air conditioners are themselves a source of carbon dioxide, they form part of a viscous cycle that has become unsustainable.

However, Gartland, who has written a book on heat islands, takes heart from the strategies available to mitigate their impact. She considers cool roofing – which utilise materials with higher solar reflectance and emittance – as the most effective means of tackling the problem.

“Cool roofing can be cost-effectively integrated into normal roof maintenance and brings many benefits in addition to reducing the heat island, such as energy savings, improved building comfort and increased roof longevity,” she says.

“ Cool roofing can be cost-effectively integrated into normal roof maintenance and brings many benefits in addition to reducing the heat island. ”

“Green roofs are also very popular since they add to the ecosystem and retain stormwater. That said, they can be pricey and not every building can support their weight.”

Gartland also advocates substituting traditional asphalt pavements – which facilitate urban islands – with either porous tarmac or lighter coloured paving that is able to stay cooler and last longer. However, the easiest and cheapest measure at the disposal of city councils is planting more trees, she says.

“Planting trees is the go-to measure, since trees bring shade, cooling, stormwater retention and wildlife habitat. However, planting a tree is relatively easy, but nurturing it to maturity takes care and effort. Faster-growing plants like vines, shrubs, and ground covers are also helpful.”

FAAB's design for Pilsudski Square in Warsaw is designed to combat the heat island effect | Image courtesy of FAAB

FAAB's design for Pilsudski Square in Warsaw is designed to combat the urban heat island effect | Image courtesy of FAAB

The design includes "wet floor" fountains to cool the air | Image courtesy of FAAB

Buildings in the square will also feature photovoltaic coatings | Image courtesy of FAAB

It also is designed to draw focus to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in the square | Image courtesy of FAAB

The area beneath the square will house Europe's largest cycle park | Image courtesy of FAAB

Hot topic: Architecture projects factoring in heat island mitigation

There are also plenty of examples of architects taking up the gauntlet to combat the heat island effect. Having recently been commissioned to redesign Pilsudski Square in Warsaw – the city’s largest quadrangle – Polish practice FAAB is constructing what it claims to be Europe’s largest bicycle park.

The thinking behind the park, explains creative director Maria Messina, is to create a vehicle-light urban ecosystem that addresses climate change and heat islands (in August, the capital city recorded its highest ever temperature of 37.2C).

“The project includes a two-storey cycle park, that will be equipped with a multi-level bicycle storage system using specialist self-service racks,” Messina wrote in a note. “It is planned to contain 15,000 bicycle spaces, with an opportunity to expand to 20,000, as well as 570 parking spaces for electric vehicles.”

“ The thinking behind Europe’s largest bicycle park is to create a vehicle-light urban ecosystem that addresses climate change and heat islands. ”

Last year, Dutch firm UNStudio partnered with Monopol Color, a Swiss paint manufacturer, to develop a new white, reflective coating system. Named “The Coolest White”, the paint is based on fluoropolymer technology that reduces the absorption and emission of the sun’s rays down to 12% – in contrast to darker materials that soak up around 95% of rays before releasing them back into the atmosphere.

The system is well-suited to metal facades and aluminium and steel structures, which have come to dominate many an urban skyline in recent years.

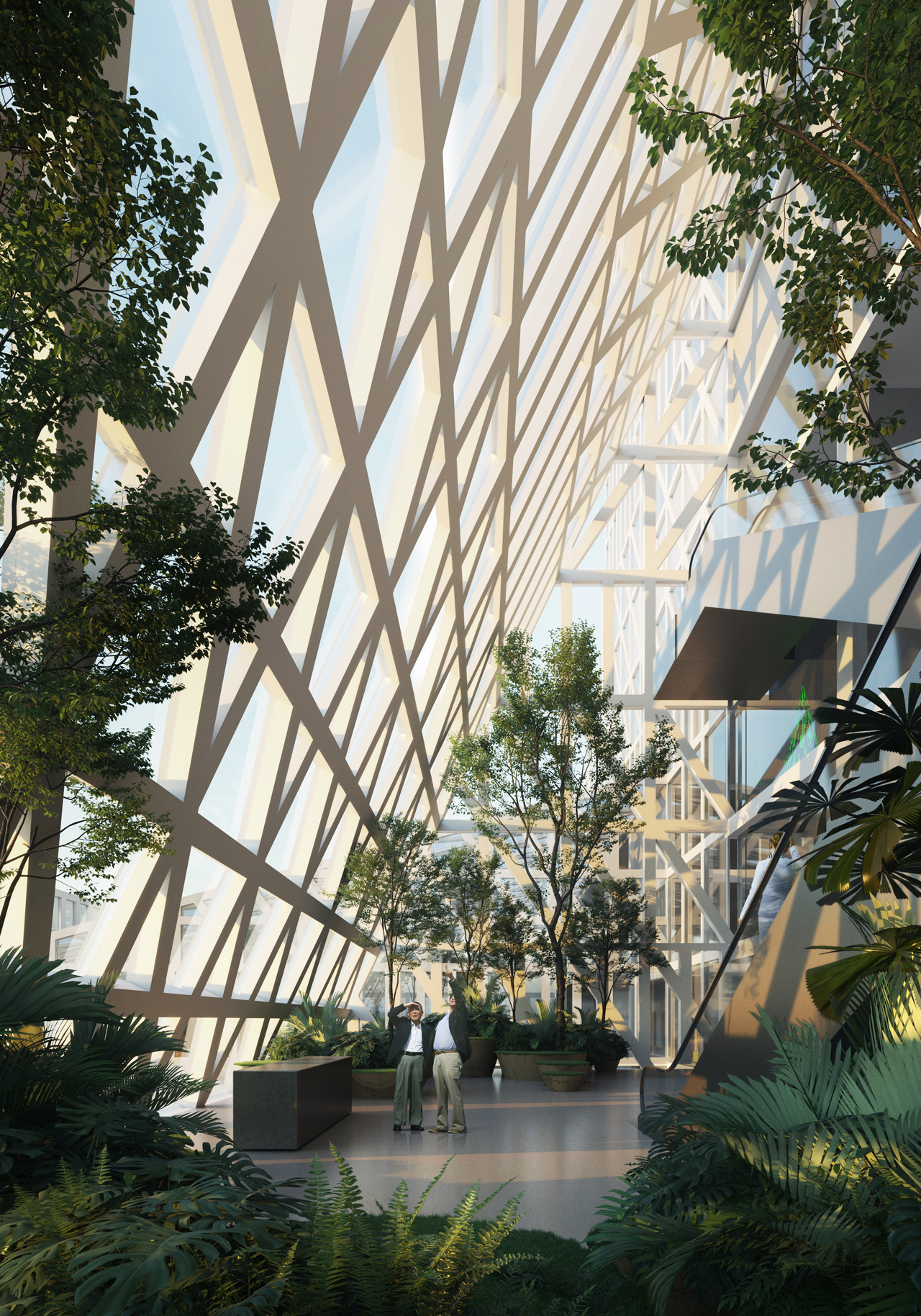

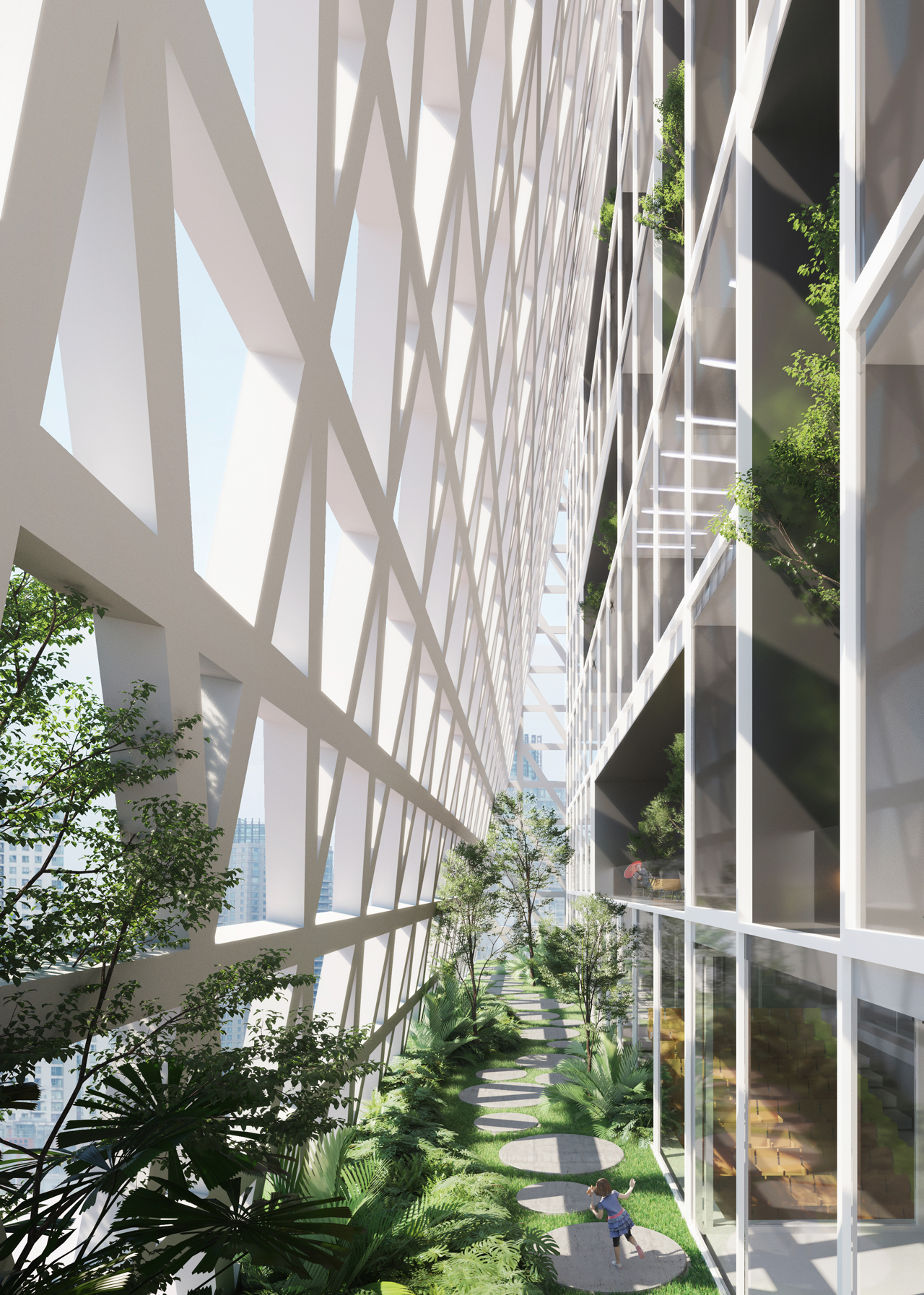

Elsewhere, fellow Dutch practice Mecanoo has incorporated sky gardens – aimed specifically at mitigating urban heat islands – into its design of the Futian Civic Culture Center in Shenzhen. In May 2018, the city, which lies in the Guangdong province of south-east China, and borders Hong Kong, saw temperatures reach 35°C – the highest on record for nearly 20 years.

Mecanoo's design for Futian Civic Culture Center in Shenzhen, China, features numerous sky gardens | Image courtesy of Mecanoo

Mecanoo's design for Futian Civic Culture Center in Shenzhen, China | Image courtesy of Mecanoo

The centre features numerous sky gardens as part of its design to combat the urban heat island effect | Image courtesy of Mecanoo

Image courtesy of Mecanoo

Image courtesy of Mecanoo

Image courtesy of Mecanoo

Image courtesy of Mecanoo

Image courtesy of Mecanoo

Image courtesy of Mecanoo

Switching off the oven: A fight for survival

According to UN projections, 2.5 billion people will be living in cities by 2050 – accounting for roughly 68% of the world’s population.

This transition will predominantly take place in Africa and Asia, where few have the luxury of turning on the air conditioning or opening the window when their apartment gets too hot.

As warned by MIT, cities in these regions run the risk of becoming man-made ovens that will stretch the limits of human survival. Innovations in the field of heat island mitigation – whether they be roof gardens, white coatings or cool pavements – could prove to be vital.