Landmarks

Swing and a miss: why do new London attractions fail to hit home?

In a city famed for a wealth of historic monuments, it is puzzling that several high-profile projects have seriously failed to hit the mark. From the recent Marble Arch Mound disaster to the costly failure of The Garden Bridge project, plans have failed to live up to the proposed potential. But why is it so difficult to develop a successful project in the city? Luke Christou investigates.

W

ith footfall in London still at just 43% of pre-pandemic levels, according to the Centre for Cities’ latest High Streets Recovery Tracker, it was hoped that the Marble Arch Mound would help to bring visitors back to the city’s busiest shopping destination.

Towering above Marble Arch, in between Hyde Park and Oxford Street, the artificial hill promised a park-like landscape and views of some of London’s most-loved spots. However, the installation, designed by Netherlands-based architecture firm MVRDV, fell well short of expectations.

The £6m project, originally forecasted to cost £3.3m, has been branded 'London's worst tourist attraction' but where did it go so wrong?

Falling flat: what’s wrong with London’s latest attraction?

For Dr Ian Mell, a reader in environmental & landscape planning at the University of Manchester, the project falls flat in many ways, due to design, planning, as well as a misjudgement of public needs.

Location

The hill’s location next to Marble Arch, Hyde Park and Oxford Street, Mell says, makes it more of a curiosity than a must-visit attraction. Of course, the 25m viewing platform provides a new vantage point to see these sights and more from above, but many visitors have found their view blocked by trees.

“Its location doesn’t really give you the wow factor view of London that you might get from the London Eye,” Mell says. “This is exacerbated in summer when the trees are in full foliage and views into Hyde Park are more restricted.”

Price

While Westminster council has since made the attraction permanently free to climb, it was initially planned to charge visitors up to £8.00 to ascend the structure.

“The initial idea to charge people to go up seems to overstate how much people want a view of Oxford Street,” Mell insists. “Moreover, given that lots of other green spaces in London are free – most, in fact – then being asked to pay becomes slightly alien to people.”

“This [cost of admission] raises a fourth point about who the Marble Arch Mound was for. Was it for wealthy or everyday, normal tourists, Londoners or other people? I’m not sure many people would pay to go up it, especially when compared to other attractions. Therefore, was it’s value focused on the wrong demographic, and if so is this why there has been a bit of a backlash?” Mell questions.

Design

Public demand and sentiment have clearly been misjudged, but the design’s shortcomings cannot be ignored. Where the original renderings showed landscapes full of trees and plants, the final construction appeared – as put by Winy Maas, a founding partner at MVRDV – “a bit modest, to put it politely”. While the mound brings something different to the area, for Mell, it doesn’t quite tick the box of innovative landscape architecture.

“I think if you’re going to invest in new landscape features, they have to have that wow factor,” Mell says, pointing to spaces such as the Olympic Park as an example of a project that found the balance between aesthetics and functionality.

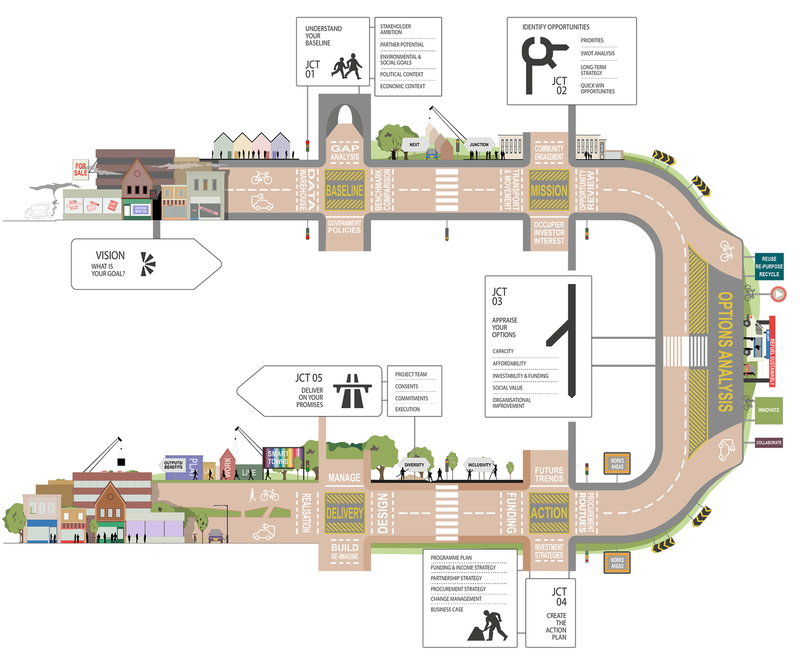

An example from the Better Towns Roadmap, a 5-step process designed to deliver achievable, actionable projects to enhance town centres and communities. Credit: Better Towns

A growing list of lacklustre attractions

The public has been particularly vocal in expressing its dissatisfaction towards the Marble Arch Mound, but this isn’t the first London attraction to have faced these problems. Rather, it joins a growing list of projects that have either failed to hit the mark or failed to get off of the ground entirely.

The proposed Garden Bridge, designed by London-based Heatherwick Studio, was intended to create a green footbridge across the Thames. With £43m of public funds already spent, the project was scrapped in 2017 over mounting estimated costs of £200m, more than triple the original estimate.

While there were few faults to pick with Heatherwick Studio’s plans, a poll by market research firm Populus found just 43% of Londoners supported the project, suggesting a lack of public demand.

High-profile projects typically suffer due to the challenge of pleasing numerous stakeholders.

The proposed MSG Sphere London, an enormous glowing orb in Stratford, would offer the city a new 22,000-capacity entertainment venue. However, the fate of the project is still uncertain, with local residents and campaign groups opposed to the potential light pollution that the project could create. Local businesses such as West Ham Football Club – occupants of the nearby London Stadium – have also questioned the plans, as have potential rivals such as AEG, operator of the O2 Arena.

Even projects like The Tulip, a planned 305-metre observation tower in London’s business district, has faced difficulty, with local authorities, architects, London City Airport, and Mayor Sadiq Khan having expressed concern.

Rather than due to any one problem, these high-profile projects typically suffer due to the challenge of pleasing numerous stakeholders. The public, government and local authorities, investors, and local businesses alike will all have their own issues and requirements that a project must successfully navigate.

“To create a new public attraction or intervention, there are many elements to get right and it’s always a potentially difficult journey, on which consultation at every stage is key,” says Pippa Nissen, director of Nissen Richards Studio.

Minimising risk in public attraction projects

For Nissen Richards Studio, a firm with a portfolio of public spaces and attraction projects across the capital, from music and events venue Printworks to various Museum exhibits, it’s important that all stakeholders are given the opportunity to play a role in the design and development of a space.

“We work hard to make sure any stakeholders or advisory groups are able to contribute to the design – and we find that at the early stage, listening is as important as designing,” Nissen explains. “Harnessing enthusiasm through consultation can short-circuit serious problems later on.”

Testing key elements of a design is also important to avoid facing problems further down the line, or producing results that fail to live up to the expectations of the initial design.

Harnessing enthusiasm through consultation can short-circuit serious problems later on.

“Everything needs to be robust and tested, so it is essential to prototype anything that is critical to the designs’ success, from the colour to the material and the functionality of anything that visitors are expected to touch and use,” Nissen says.

Safeguarding budgets is also important. To avoid wasteful spending and mounting costs, Nissen Richards Studio picks out essential elements of the projects to focus on and simplifies the rest.

“What is it about the visitor attraction and the experience that encompasses the idea, and what can be background and support this? Therefore, in our concept stage, we think as broadly and excitingly as possible. Out of this stage, we find a gesture that will be key to the final design – light, dark, moving elements, material qualities, artworks etc – and then simplify everything else around this, so that the experience is concentrated on a particular moment which is then worth spending money on,” Nissen explains.

Projects can overcome a slow start

Of course, even the most well-planned projects can produce a negative reaction – “In the final analysis, whatever we do as clients, architects and designers, there is always an element of unpredictability as to how results are received,” Nissen says. “This partly depends on whether public money is involved and also whether the media sets itself against the project.”

Yet, initial opinions can be changed after a project has had time to prove its worth. Two decades ago, current Prime Minister Boris Johnson suggested that the Millennium Dome should be blown up as ‘public humiliation’ for its underwhelming launch. Still standing, the structure today ranks among the world’s best live entertainment venues.

There is always an element of unpredictability as to how results are received.

“The furore over the Dome is long-forgotten now the O2 is such a successful entertainment venue, whilst the London Eye has gone from being much-debated to much-loved,” Nissen points out.

With British sculptor Anthony James’ LED light display soon to take over Marble Arch Mound’s temporary exhibition space, providing another reason for visitors to reach the top, perhaps there is still hope for Oxford Street’s artificial hill.

Main image credit: Travers Lewis | Shutterstock.com