After the Flood: The Pioneering Architects Embracing Flood-Conscious Design

A surge in extreme weather conditions is requiring architects to increasingly take flooding into account in their designs. Elliot Gardner takes a look at some of the projects pioneering in this area, and hears from some of the architects involved about the best practices for flood-conscious design

Frequent coastal and riverside floods and severe cloudbursts across Europe and America have led to an increased focus on flood-centric design. It’s becoming more and more common for architects and designers to incorporate flood defence, in some capacity, into their structures.

Between 90-100% of climate experts now agree that human-caused global warming is an issue now facing humanity, and a warmer planet means higher sea levels and more extreme weather conditions. In May 2017 scientists claimed that even small increases in sea levels could double the frequency of severe coastal flooding in most parts of the world. Dire news, then, for those towns, cities and structures located on the shoreline.

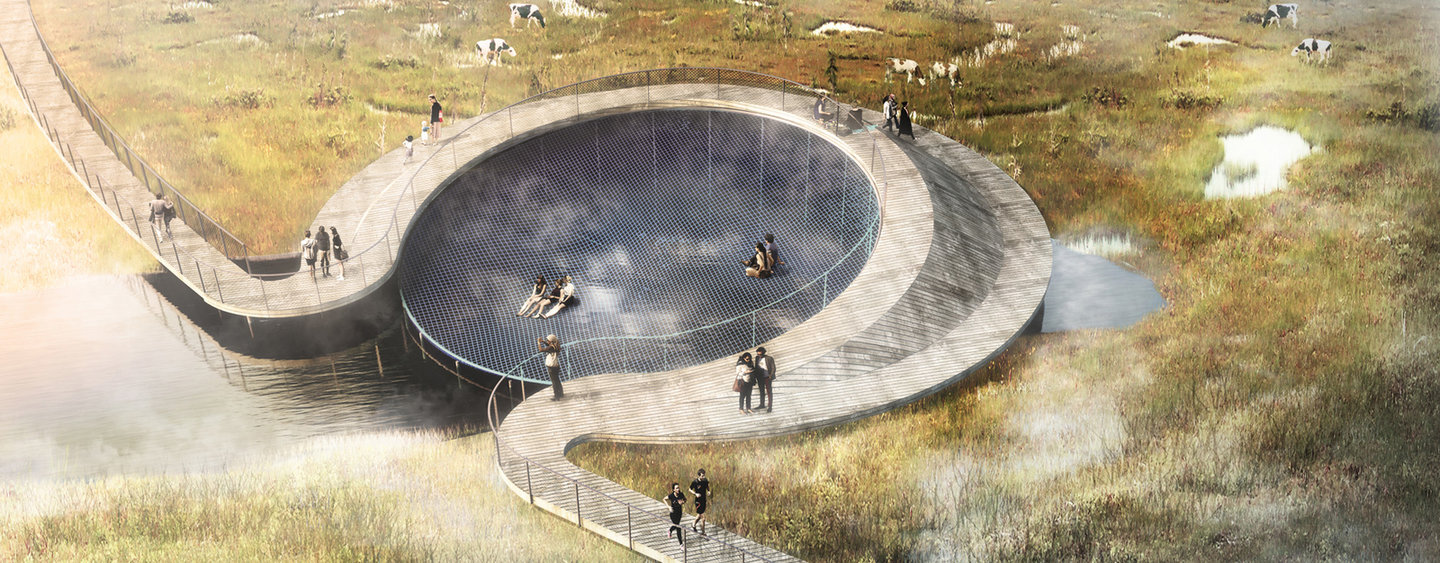

Embracing the water – C.F. Møller’s Stork Meadow

Storkeengen, or Stork Meadow, from C.F. Møller stands as an example of a city addressing the threat of floods and simultaneously incorporating landscape solutions into wider city developments.

Randers is Denmark’s sixth-largest city and is located on the country’s Jutland peninsula, close to the Gudenå River. Stork Meadow is the first in a series of projects planned in the area in upcoming years, and is part of ‘Climate Ribbon’, a wider initiative with the aim of making the city more resilient against storm surges without the need to create water barriers.

The project is essentially a nature park designed to flood, utilising nearby wetland meadows to handle excess storm water. In addition, routes are planned throughout the town in order to direct rainwater from roofs and roads outside the city to the park, away from key infrastructure.

“ The classic problem when you create flood protection is that you end up creating barriers between the water and the protected area. ”

“The classic problem when you create flood protection is that you end up creating barriers between the water and the protected area. We considered how to overcome this ‘barrier effect’, and decided on turning that wall or dyke into a whole barrier area,” explains C.F. Møller associate partner Lasse Vilstrup Palm. “We wanted to approach flood protection with a much broader view of the problem, keeping in mind all the urban, landscape and nature challenges in the project area.

“The Stork Meadow project is described locally in the press as a nature park that gives back to the city, and not a flood protection project at all.”

According to Palm, there has been an intense increase of focus on the flooding issues over recent years, with public programmes looking beyond simply building a wall to keep the water out.

“It’s a basic issue here in Denmark. In low-lying areas it’s something that needs addressing, and wherever possible integrated into natural surroundings, because flood protection takes up a lot of space.”

Images courtesy of C.F.Møller

The Dutch approach – NEXT Architects’ Zalige Bridge

The Netherlands has a long history of incorporating a flood-centric approach into its designs. Around a third of the country is below sea level, and a complex system of dykes and pumps keep the country from flooding. “We have a long history of fighting the water in the Netherlands, as we live in a delta. I think it’s part of our culture to deal with it,” comments founding partner at NEXT Architects Michel Schreinemachers.

As part of the Dutch ‘Room for the River’ programme, an island was created by redirecting water near the city of Nijmegen. NEXT was tasked with the creation of a pedestrian bridge to link up to this new urban river park, which was designated for nature development and recreational use.

“ You can’t just design for now; we have to design it for 100 years from now. ”

The ‘Zalige Bridge’ was designed to celebrate the country’s relationship with the water. Instead of a straight bridge, the designers instead opted for a meandering route, and when the bridge inevitably floods in times of high rainfall or raised river levels, the concrete benches lining the ground-level areas of the bridge instead becomes a series of stepping stones, still providing a route over the water.

“We really wanted to make this more than just a connection to this island,” says Schreinemachers. “The project runners were worried the headlines would report on a bridge that can’t even be used. We said ‘we’ll get you those headlines, but they’ll be positive’.”

Describing the difficulties associated with flood design, Schreinemachers went on to express the careful balance that needs to be struck between elegance and functionality. “It’s sometimes hard because of all the materials you need to reinforce the structure, but we try elegant designs where we can. You can’t just design for now; we have to design it for 100 years from now. It’s the problem we face - to create something that's elegant but will stand the test of time.”

Images courtesy of NEXT

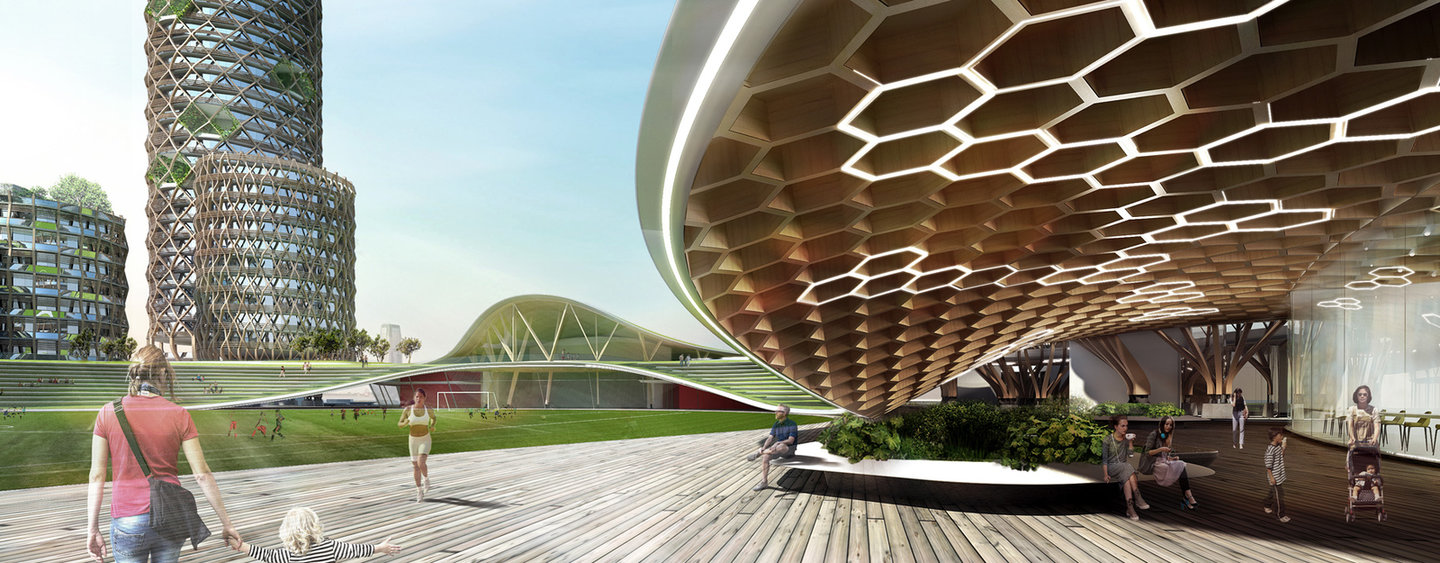

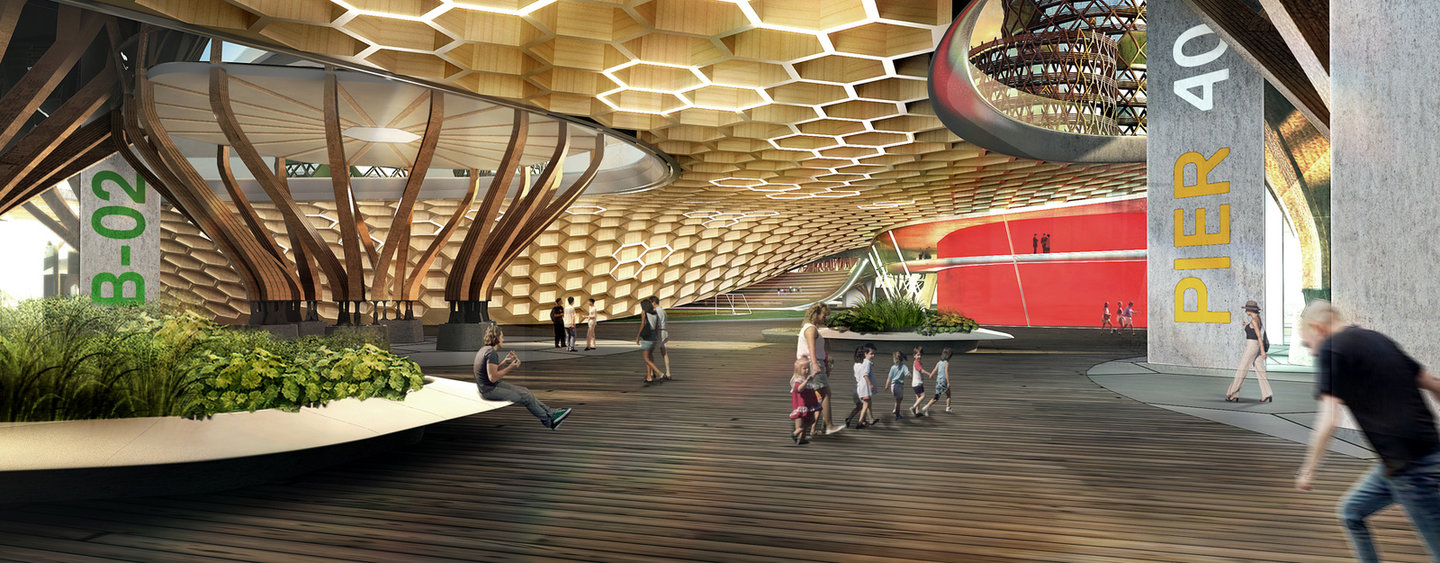

A look to the future – DFA and Pier 40

Architects are increasingly having to embrace the water. Over the last two decades, the rate at which the oceans are rising has nearly doubled, to 3.2mm per year. This puts pressure on cities such as New York, whose close connection to the Atlantic has led to projections that the city can expect hurricane Sandy-like floods every five years by 2030.

The sea level of New York City is expected to rise by 50-75in by 2100, leading design and architecture firm DFA to envision what it believes will be the future of flood resistant architecture in the city. DFA has publicised its re-design of River 40, the largest pier on the Hudson River, for the year 2100, conjuring up images of eco-friendly tower blocks surrounding recreational and commerce areas, all designed with the rising tide in mind.

“ Future flooding is a reality that still has not fully been accepted. ”

While Pier 40 would be created with flooding and the environment in mind from the offset, the design has caught attention with its creative solution to what to do when water levels reach the land. The retail, theatre and sports districts are all designed to flood around the year 2050, and floating landscape pods will take their place, complete with oyster beds and recreational areas of their own. The pods will also absorb wave energy, protecting the tower structures during storm surges.

Designing for both the present and future has its challenges though, as principal architect Laith Sayigh explains: “The basic infrastructure of the buildings has to allow for the tidal surges in the interim years as the sea levels rise. It is not simply an overnight change - all lobbies, public areas and retail spaces had to be designed to allow for this. “

In creating the designs, Siyigh has been quite vocal about the problems flooding poses to the city, saying “I feel [future flooding] is a reality that still has not fully been accepted. For example, large swaths of the West Side Highway will be submerged and have been as we have witnessed. Large areas of the park and landscape do not seem to respond to the immense changes and challenges ahead.

“New buildings designed on around the edges of lower Manhattan, the most vulnerable areas, are still not being designed with a 50 to 100 year plan - and while costs escalate for much of this property, little seems to be done to ensure its resistance to imminent flooding.”

Images courtesy of DFA