Planning

How will the pandemic shape mixed-use spaces?

The Covid-19 pandemic has shifted focus from city centres to towns and local high streets as many people spend more time working in their homes. Luke Christou finds out how this trend could impact the planning and development of mixed-use spaces.

O

nce bustling urban spaces have been transformed into ghost towns amid the pandemic. Retail footfall fell by 43% on average throughout 2020, while the reopening of shops and hospitality venues has so far failed to spark a return to pre-Covid numbers.

However, as life moves closer to home, local centres will have a greater role to play, providing space to shop and socialise away from our home offices. While the UK Government has called for a gradual return to the office over the summer, widespread remote working practices are likely to persist, with almost all of the UK’s 50 biggest employers set to embrace hybrid working models.

“Mixed-use spaces have a significant role to play in responding to changing work and life trends,” says Alex Craggs, associate director and urban design specialist at planning consultancy Marrons Planning.

“People are discovering how remote working can benefit them in the new normal. It offers flexibility and, in many cases, people feel like they are more productive. However, there is a risk of social isolation and managing mental health has become increasingly important.”

Prioritising health and wellbeing

During bouts of social distancing, architecture has placed greater importance on designing to protect the health and wellbeing of occupants, from pandemic-friendly social spaces to green hospitals, schools and offices. As we move past the pandemic, health and wellbeing could remain a priority in the future development of mixed-use spaces.

“Mixed-use developments should put people’s physical and mental health and wellbeing at the forefront of design,” Craggs says. “It’s important that they enable people to feel connected to society, to feel part of a community, and to live healthier, happier lives.”

With long-term exposure to air pollution shown to increase the fatality risk of Covid-19, environmental sustainability is likely to play an important role in this. In a recent BCG survey, 70% of respondents were more aware of humanity’s environmental impact than before the pandemic, with 75% more concerned about environmental impact than health issues.

Mixed-use developments should put people’s physical and mental health and wellbeing at the forefront of design.

“In the next few years there’s got to be a massive focus on sustainability, just because we don’t have an option anymore,” says Olivia Paine, asset lead within the asset and workplace sector for HLM Architects. “Sustainability is important for all of the councils we’re working with at the moment.”

Rather than serving polluting petrol vehicles, for instance, future developments could be designed to better serve electric vehicles, while more environmentally focused areas may choose to go down the vehicle-free route.

During the pandemic, councils across the UK implemented a wave of initiatives to reduce vehicle pollution in urban centres and reclaim space for pedestrians, with places such as Brighton considering plans to ban cars from its centre permanently.

The post-Covid town centre

With workers avoiding busy inner-city areas, the shift towards remote and hybrid working models is likely to drive focus away from city centres towards periphery towns.

“What we’re seeing is that the focus in mixed-use development is shifting from being incredibly city-centre focused because everyone is staying home and relying heavily on town centres,” says Paine.

“People are certainly waking up to the idea that they could actually have a good work-life balance if their high street could provide it.”

Mixed-use developments that lack the amenities to serve local populations will need to adapt. Paine expects to see an increase in local workspace in towns and high streets, for instance, to provide space to work away from home without the inconvenience of commuting to a city. Bringing greater footfall to town centres, this will help to breathe new life into the local retail and hospitality venues that have barely survived the pandemic.

People are certainly waking up to the idea that they could actually have a good work-life balance if their high street could provide it.

“Having workspace on a local high street will bring people back to independent businesses and allow for a night-time economy to bring everyone together,” Paine says.

Covid-19 has also caused a drastic decline in the use of public transport. Bus use fell by 90% during the first lockdown and National Rail usage dropped by 96%. According to Craggs, this trend could outlast the pandemic, with sprawling transport facilities becoming less important should future mixed-use areas provide all the amenities residents need close to home.

“People would likely welcome this change long-term if things like better public amenities, local shops and high-quality open spaces were on their doorstep and travelling wasn’t such a necessity.”

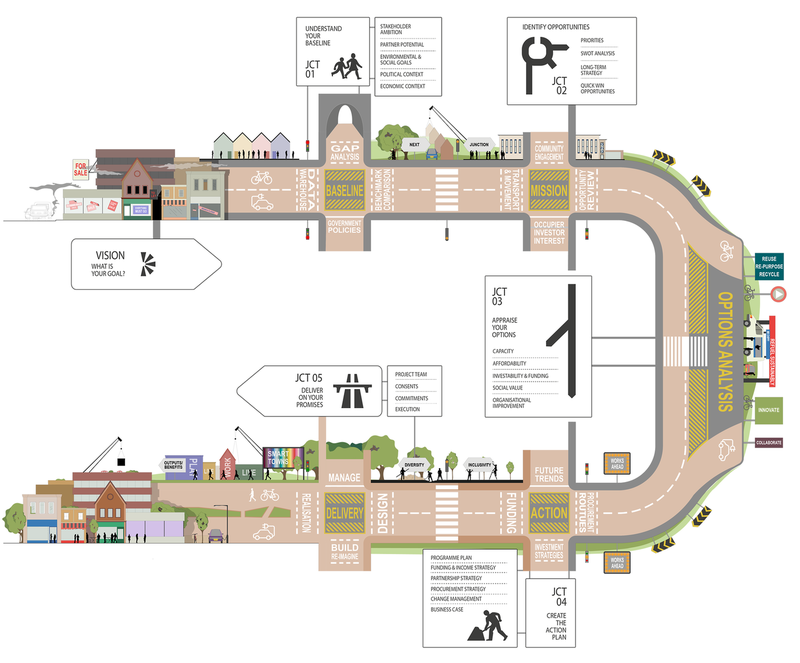

An example from the Better Towns Roadmap, a 5-step process designed to deliver achievable, actionable projects to enhance town centres and communities. Credit: Better Towns

No ‘one size fits all’ solution

There are often few differences between one high street and the next. However, this ‘one size fits all’ solution, which fails to consider the specific needs of the local population, doesn’t work for every town, according to Paine.

“I think we’ve been going down the route of every single town having a certain type of traffic, a certain sort of middle-of-the-range retail,” she says. “They’re all using the same solution, which doesn’t drive any sort of community aspect and doesn’t encourage people to care about their town centres.”

HLM Architects, as part of a consortium with asset management solution provider Real Estate Works and data consultancy Didobi, has developed a solution to address this reliance on a one-size approach.

After sitting on the idea for several years, Covid-19 proved to be to catalyst for the consortium to push ahead with the Better Towns Roadmap, a five-stage process to identify, fine tune, and implement short, medium, and long-term regeneration goals that can make a ‘meaningful difference’ to mixed-use spaces such as town centres.

Better Towns consortium works with authorities throughout the urban regeneration process to take full stock of an area's needs and gather data to identify priorities and opportunities specific to the area.

While urban planning is often brief-driven, the Better Towns consortium works with authorities throughout the urban regeneration process to take full stock of an area's needs, communicate with residents and stakeholders and gather data to identify priorities and opportunities specific to the area.

“We had a tool that had been designed and could actually help a lot of people coming out of this pandemic, because it was clear right at the very start that this was going to have quite an impact on the way we view town centres,” Paine explains.

“The roadmap is intended to be a very clear, transparent process that shares the knowledge of the private sector and our expertise with local authority clients, allows them to understand the processes that are going on, and leaves them with the tool to carry on building and monitoring.”

The consortium is currently working with local authorities in Surrey, Kent and Sheffield, helping clients to develop action plans to aid their recovery from Covid-19. While there are still challenges, notably conflict between various stakeholders, data proves difficult to disagree with.

“It’s hard to argue with data,” Paine says. “If you demystify the process and they understand they’re not being confronted by something at random, it becomes a lot easier.”

Mixed-use developments will undoubtedly change in the pandemic’s wake, but there’s no single answer to how. That will be different for each development, specific to the needs of those that use the space.

Main image: Illustration from the Better Towns consortium’s roadmap. Credit: Better Towns