Economy

Surviving a crisis in architecture: lessons from HOK

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on the architecture industry, but there are strategies that can help. Luke Christou speaks to Patrick MacLeamy, former CEO of global architecture firm HOK, about how the practice re-built its approach during the previous recession, and what lessons other architects can learn.

P

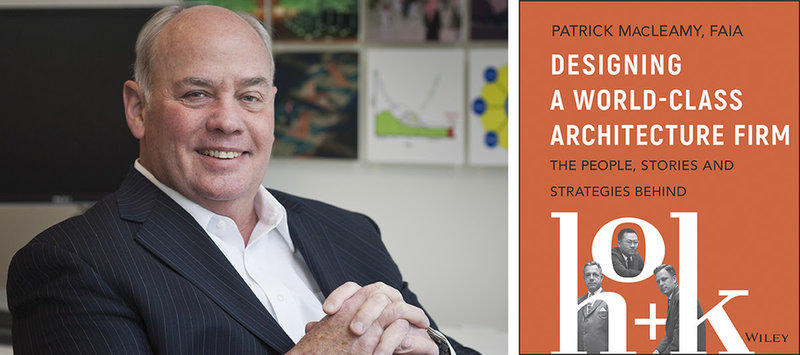

atrick MacLeamy, former CEO of global architecture firm HOK and author of Designing a World-Class Architecture Firm: The People, Stories, and Strategies Behind HOK, knows a thing or two about surviving hardship in the architecture industry. Having spent over 50 years with HOK, working his way up from junior designer, MacLeamy witnessed numerous crises with the firm before leading it through the financial crash of 2008.

With the Covid-19 pandemic having a similar, devastating impact on architecture, MacLeamy and HOK’s story offer a blueprint for firms to follow as they seek not only to recover from the current crisis, but to prepare for the next one.

“My advice is the same now with the coronavirus as my advice was during 9/11 or the financial meltdown of 2008,” MacLeamy says. “If you’re the leader of a firm, whether it’s large or small, the first thing you need to do is not just wring your hands. You need to run at this problem.”

Designing a World-Class Architecture Firm offers architects insight on the successful running of an office, based on MacLeamy’s experiences at HOK. Credit: HOK | Patrick MacLeamy

How to overcome a crisis

In hard times, all businesses consider where they can cut expenses and conserve cash. As the Architecture Billings Index (ABI) has shown throughout 2020, architectural work is often one area that suffers. “If our clients get a cold, the architects get pneumonia,” as MacLeamy puts it.

The first thing firms should do, MacLeamy says, is to communicate with your clients to gain an understanding of how the downturn is likely to impact your business. This should be done immediately and directly.

“You don’t wait a week and you don’t send an email out to all of them. You call them so that you reach out personally, directly,” MacLeamy says. “How are you? How’s your company? How’s your family? Show you’re sincerely interested in them before you ask about continuing your work.”

Next, leaders must communicate with their employees, who will undoubtedly be worried about their own future. Even if you don’t have answers immediately, company-wide meetings offer an opportunity for staff members to ask questions and hear how the firm plans to overcome the situation.

“Be truthful, because people are not stupid. Tell them truthfully what you know and begin to give them an idea of what your thinking is,” MacLeamy says.

You work hard to recruit these people and to train them up, so you don’t just dispose of people with abandon.

Leaders must also think about the financial impact of the crisis and consider how much cash is available, how long it will last, and whether there is room to stretch it further.

You should be thinking about redundancies from the very beginning, carefully considering who you can afford to lose. However, such measures should only be considered when other options, such as delaying payment of a percentage of wages, have been exhausted.

“The biggest resource the firm has is what? It’s people,” MacLeamysays. “You work hard to recruit these people and to train them up, so you don’t just dispose of people with abandon. You’re deliberate and careful about it.”

Should redundancies become unavoidable, firms should make all necessary cuts at once, and communicate to staff that there are no plans to make further redundancies.

Learning to survive

The reason many firms struggle, MacLeamy believes, is because many never learn how to operate a business. Those that are ill-prepared, or unwilling to learn, are those most likely to go under during a crisis.

“Most architects are terrible business people,” MacLeamy explains. “We’re not taught this in school, we’re taught about design and the history of architecture and the technical aspects of design and construction.If you want to build a strong firm that will survive a coronavirus, a financial meltdown, a recession, or a time of inflation, you have to know the business basics.”

In Designing a World-Class Architecture Firm, MacLeamy talks abouta number of rules that he developed during his time at HOK to monitor the firm’s financial health.

For example, he believes firms should spend no more than 50% of its annual turnover on basic salaries. This leaves enough to pay benefits and bonuses, deal with the costs of running an office, and maintain a healthy profit margin of at least 15%.

“Most architects get into trouble by having too many people for the fees they have,” MacLeamy explains.

If some client doesn’t pay and you’ve got yourself extended, that can break a firm.

At HOK, a simple metric was used to determine the state of a particular office: firms that maintained a backlog of work equal to around ten months’ worth of wages were stable. If the backlog was less, the firm was shrinking, and greater marketing efforts were needed to turn it around.

MacLeamy also believed that architects need to improve their payment collection processes. Of course, this is an issue that all businesses face. In the UK, collection within 30 days is typically seen as good. Yet, studies show that businesses wait as long as 120 days to receive payment for their work. This, pandemic or not, can have serious consequences.

“You don’t even have to have coronavirus,” MacLeamy says. “If some client doesn’t pay and you’ve got yourself extended, that can break a firm. I’ve seen it.”

Rather than waiting for clients to pay, firms need to be chasing up missed payments, resolving issues that may arise, and turning money owed into cash.

HOK was appointed lead architect for the redevelopment of London’s St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, which was completed in early 2016. Credit: HOK

Don’t wait until crisis hits

Like anyone, MacLeamy had to learn these lessons through experience. Upon taking over as HOK’s CEO, he inherited a firm with poor payment collecting processes, a maxed-out line of credit, and just 60 days to begin repaying the debt. Failure to do so would have likely bankrupted the firm.

He set about chasing debts, paying off the credit line, and putting the financial practices in place to safeguard against future incidents.

Offered a larger line of credit, HOK didn’t make the same mistake twice. Instead, the firm started making regular deposits into a savings account. After three years, the savings exceeded the firm’s line of credit, providing funds for the firm to fall back on in hard times.

“If all your clients said we’re through, how long could you survive? Ninety days is a minimum, but it’s far better if you can accumulate cash for six months,” MacLeamy says. “Too many architects fall victim because they haven’t taken these basic steps to be prepared for a crisis. Once you’re in it, then it’s a little late to be putting aside money for a rainy day.”

By diversifying, firms can be better prepared should work dry up in a particular part of the market.

The former CEO stresses the importance of forward planning, and not only financially. Rather than focusing on one type of client, MacLeamy advises firms to take on a range of clients and project types, including in the public sector.

“Those clients exist on taxes,” MacLeamy explains. “Governments, when there’s a financial crisis, what do they do? They tend to spend more to try to stimulate the economy.”

Firms should also diversify, rather than focusing on one building type. HOK, for instance, added sports architecture to its portfolio in the early 1980s, and today specialises in a range of areas, such as aviation, government, healthcare, residential and more. By diversifying, firms can be better prepared should work dry up in a particular part of the market.

Embracing positive change

At HOK, MacLeamy found that financial struggles often led to corner-cutting. Offices that were struggling would often refuse to upgrade computers at a time when speeds were crucial, while others would copy and use their AutoCAD software illegally.

A recent Capital One study found that stress typically leads us to poor decision-making, and with the pandemic having caused a significant decline in the mental health of architects, according to a recent RIBA survey, many will be tempted to cut corners to ease the burden. However, as the firm leader, it’s your responsibility to build and maintain a strong foundation, reputation, and culture throughout the business, MacLeamy says.

While the pandemic has presented challenges to all businesses, there is also an opportunity for firms to learn and improve. As the UK was thrown into lockdown last March, 30% of firms admitted that they were experiencing communication difficulties. Now, with videoconferencing practices established, firms can begin to enjoy the benefits of a more remote workforce.

I think architecture and design need to have a central place in our society. We’ve lost a lot of that, and a lot of it is because firms don’t know how to operate properly.

Particularly for larger firms, such technology offers an opportunity to assign your best people to a project, regardless of where in the world they or the client is located. MacLeamy recalls HOK’s work on the St Bartholomew's Hospital project in London.

Video conferencing equipment, implemented soon after he took on the CEO role, was used to provide healthcare expertise from the New York office to those in London, ensuring that clients received the best possible service without the need for frequent transatlantic flights.

“The ability to work across time zones and from one office to another was something I fostered because it focused on clients,” MacLeamy explains. “We combined local capacity – the London office knows about how to design and build in the UK – with healthcare expertise from New York. It’s a combination of the best that we can offer a client, and that requires remote working.”

Covid-19’s impact will be just like any other crisis. “The good firms will get better because of this, and the firms that are not prepared will not survive,” MacLeamy says. Which category a firm falls into isn’t based solely on design, but also how well they operate as a business.

“I think architecture and design need to have a central place in our society. We’ve lost a lot of that, and a lot of it is because firms don’t know how to operate properly. I don’t want firms to fail,” MacLeamy concludes.

Main image: MacLeamy, pictured here in 1970 joined HOK as a junior architect in 1967 and spent over five decades with the prestigious firm. Credit: HOK