Urban development

Building an urban community:

the benefits of co-living

The pandemic has revealed a growing desire for communities closer to peoples’ homes, particularly given the high living costs and crowded conditions in many cities. Alex Love explores some of the projects aiming to provide a solution and hears about the benefits from the architects involved.

A

sense of community is often considered to be lacking in big cities, yet the Covid-19 pandemic has increased awareness of the benefits of communities, highlighting the need for more human contact.

The concept of co-living solves the problem of isolation in cities by creating a community with ample opportunities to meet new people. Residents have their own private rooms with en-suite bathrooms, but have access to communal areas, such as kitchens, roof-top gardens and breakout spaces where they can interact with others.

“We can see co-living within the shared economy movement,” says Vangel Kukov, design applications technologist at Perkins&Will. “But also, within the context of connectivity, I think that the more connected we are, the more disconnected we are from real world communication and relationships. Concepts like [co-living] bring us back together. By creating co-living schemes that are multi-generational as well, so we reconnect with different generations, and each of us helps with different experiences and knowledge.

A different way of living

Co-living may appeal to working professionals seeking a different way of life. Most developments offer all bills included in the rent, as well regular cleaning, membership to an on-site gym, and invites to social events. Many sites also offer areas where people can work, an aspect that could become more important with the rise of remote working as a result of the pandemic.

“It's a different way of living, but it's been around for many years - people housesharing,” explains Tim Chapman-Cavanagh, director at Assael Architecture, which has been involved in the design of a number of co-living projects. “But it's all of those things that we've learned that are difficult within those house shares, and trying to eradicate some of those. And then it's also those chance meetings as well, you don't know who your neighbour is and you've got those lounge areas, the roof, terraces, and all of that.”

The Collective is one organisation offering co-living accommodation in London and New York, with plans to expand into other countries. Despite the team behind it emphasising affordability, residents can expect to pay approximately £200-£280 a week in London. Lengths of stays are flexible. Residents of The Collective accommodation also have the option of moving from a block in London to New York, or other future sites, simply by picking up the phone.

It is hoped that co-living developments, such as the Nineyards development in Kingston pictured here, will help revive struggling town centres. Credit: Assael Architecture.

Urban regeneration through communities

With local authorities looking for ways to revive struggling town and city centres, co-living schemes could prove to be an engine for regeneration. The first of three London co-living schemes by Viewranks Estates and Assael Architecture has recently been approved by Kingston Borough Council.

The 200-bedroom development on Fife Road in Kingston town centre will be managed by Nineyards Living. As with much of the UK, the town has experienced a diminishing high street in recent years. It is hoped that increasing the number of people living in town centres will keep revenue in these areas and provide a lifeline for local businesses.

“What has been quite shocking in the last couple of years is the slow decline of the high street. It wasn't as bad when we started this project,” explains Chapman-Cavanagh. “But what was quite interesting is that as we went to site, we did walk arounds, and we also took a series of photos, we noticed quite early on, just one shop after the next was slowly closing.

“One of the key benefits that we wanted to pursue was really to get that footfall back into Kingston town centre. What we wanted to do was to try and obviously make a community within the building, but also really think about the community, which is slowly diminishing in places like this.”

Where's the in-between in getting a one-bedroom flat or sharing a flat with somebody or just staying in a four or five-bedroom house?

In addition, there is a focus to try and keep students in the Kingston area after they graduate.

“One of their key drivers was: where is the middle ground between you leaving student halls or you house sharing in a five-bedroom house? Where's the in-between in getting a one-bedroom flat or sharing a flat with somebody or just staying in a four or five-bedroom house? And that's where co-living really pitches itself,” adds Chapman-Cavanagh.

Nineyard Kington’s design is influenced by art deco. Approximately 62% of standard rooms measure 16.6m2, with 30% being ‘plus’ rooms that are 18m2, and 8% are accessible rooms of 25m2. Rooms will feature their own bathroom and small kitchenette. The larger ‘MasterChef style’ kitchen area is available for communal use on the ground floor, with a gym and cinema in the basement. The roof features a communal garden with seating areas.

The building will feature an old New York-style fire escape on its exterior, with extended landings on the upper floors providing another breakout space with views of the Thames and Richmond Park.

The £60m Kingston project is also being designed to encourage cycling, with a focus on easy access and storage facilities for bikes. Rent is expected to start at around £275 a week.

Co-living concepts such as Perkins&Will’s Arroyo aim to create a thriving community, but also benefit the city population in the surrounding area by allowing them to share certain facilities. Credit: Perkins&Will.

Future visions for co-living

In the years ahead, there is likely to be an increased focus on co-living concepts as cities try to house growing populations.

Global architects firm Perkins&Will recently held its annual Phil Freelon Design Competition – named in memory of a former Perkins&Will director – to address this worldwide housing crisis.

The winning entry came from Perkins&Will’s London studio, led by design applications technologist Vangel Kukov and senior interior designer Hala El Khorazaty. The team’s proposal transformed an industrial site in New York City’s West Village of Manhattan into a co-living complex that celebrates diversity.

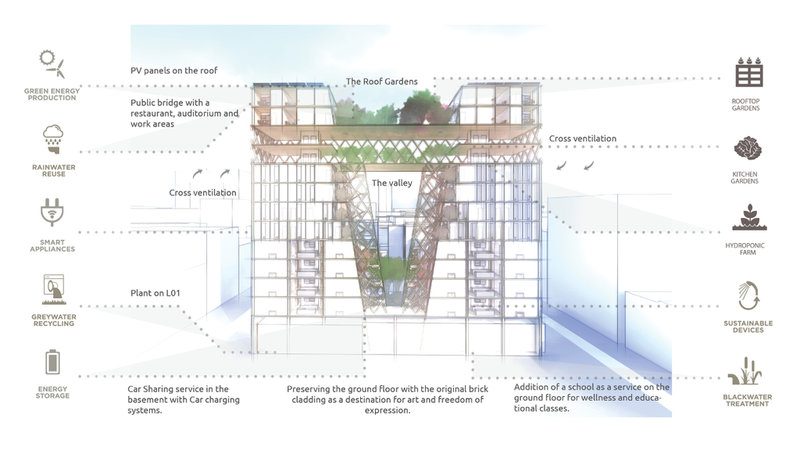

The design took inspiration from the idea of ‘arroyo’, which means a dry environment that is transformed by rainfall to then teem with life. The design features two towers joined by bridge gardens on the upper floors and what the team calls ‘the valley’ lower down.

A design by Perkins&Will’s London team transforms an industrial site in New York’s West Village into a co-living building with a circular carbon footprint. Credit: Perkins&Will.

The concept has been designed to have a circular carbon footprint, using the foundations of the existing building on the site.

“The foundations are where most of the carbon footprint of the building is hidden anyway, explains Kukov. “And one other thing that we're doing is that we're using mass timber that can be fully disassembled and reused or recycled at the end of its lifetime. When this timber structure is sustainably and locally sourced as well, then we will have a building system that acts actually as a carbon sink and can offset some of the carbon footprint of the buildings over its lifetime.”

The design aimed to debunk the notion some have of co-living as essentially a hostel for professionals.

Upper sections of the building are made from glued laminated wood (glulam) and cross-laminated timber in a diagonal, criss-cross design. The roof features solar panels; rainwater is reused and wastewater is treated.

In addition, the design takes into account the need for the wider public to feel welcome within certain communal areas, instead of the building being limited solely to residents.

“We enforce the concept of bringing the public through the space from the ground floor, where we have the historical site, and then creating a burst in the middle of the two towers to take them all the way onto the tenth and 11th floor where there's a public access bridge and a community garden,” El Khorazaty says. “So it's inviting the community, not just in one area and bridging them off, but also inviting them inside the space itself; to be able to enjoy the services that Arroyo could provide.

“We have a harvest farm on the rooftops so that, if someone wanted to harvest something, they could plant certain crops, fruit and vegetables, and then send it to the harvest kitchen in the public space. Then someone from the same community could cook a meal and someone from the public could easily purchase something from there.”

The team also proposed an app, where residents can get rent reductions by helping out around the building.

El Khorazaty adds that the design aimed to debunk the notion some have of co-living as essentially a hostel for professionals.

“I think there's a misconception about co-living that it's meant as dorms for adults. So they're in this transitional mode in their life until they reach that point of success where they can own something. And that is not how we looked at it all; we wanted to look at it as a community where everyone is impactful,” she says.

Main image: View into a room in the Nineyards co-living development in Kingston. Credit: Assael Architecture.